The Inner World of Beethoven

How did Beethoven’s desperate personal circumstances – his deafness, social isolation, frustrated love – colour his music? Stephen Johnson delves into the composer’s innermost being

Lonely prince of a realm of spirits’: that’s how one of Thomas Mann’s characters sums up the older, late-period Beethoven in his novel Doctor Faustus. Of course, it’s a romanticised image, as Mann himself would have been well aware; but it opens the door on an important truth. The Beethoven who hymned the brotherhood of man with such desperate intensity in his Ninth Symphony, who strained at the borders of the expressible in his effort to embrace ‘you millions’, must by this stage of his career have been one of the loneliest figures in the history of Western classical music.

Beethoven always had a tendency towards solitude and introspection. His lifelong friend Stephan von Breuning remembered him at a very young age taking solitary walks or disappearing into his own thoughts in company. It’s not very surprising when one learns that Beethoven’s father, Johann, was an alcoholic bully, who beat little Ludwig savagely and thought nothing of dragging him out of bed in the middle of the night to play for his drunken cronies. Children of abusive parents often find an escape route by retreating into a dream-world. Conversely, they can find the outer ‘real’ world hard to deal with. As an adult, Beethoven was often irascible and, inevitably, he developed a problem with authority figures, from his teacher Haydn to the aristocratic patrons on whom he partly depended, for encouragement as much as for financial support.

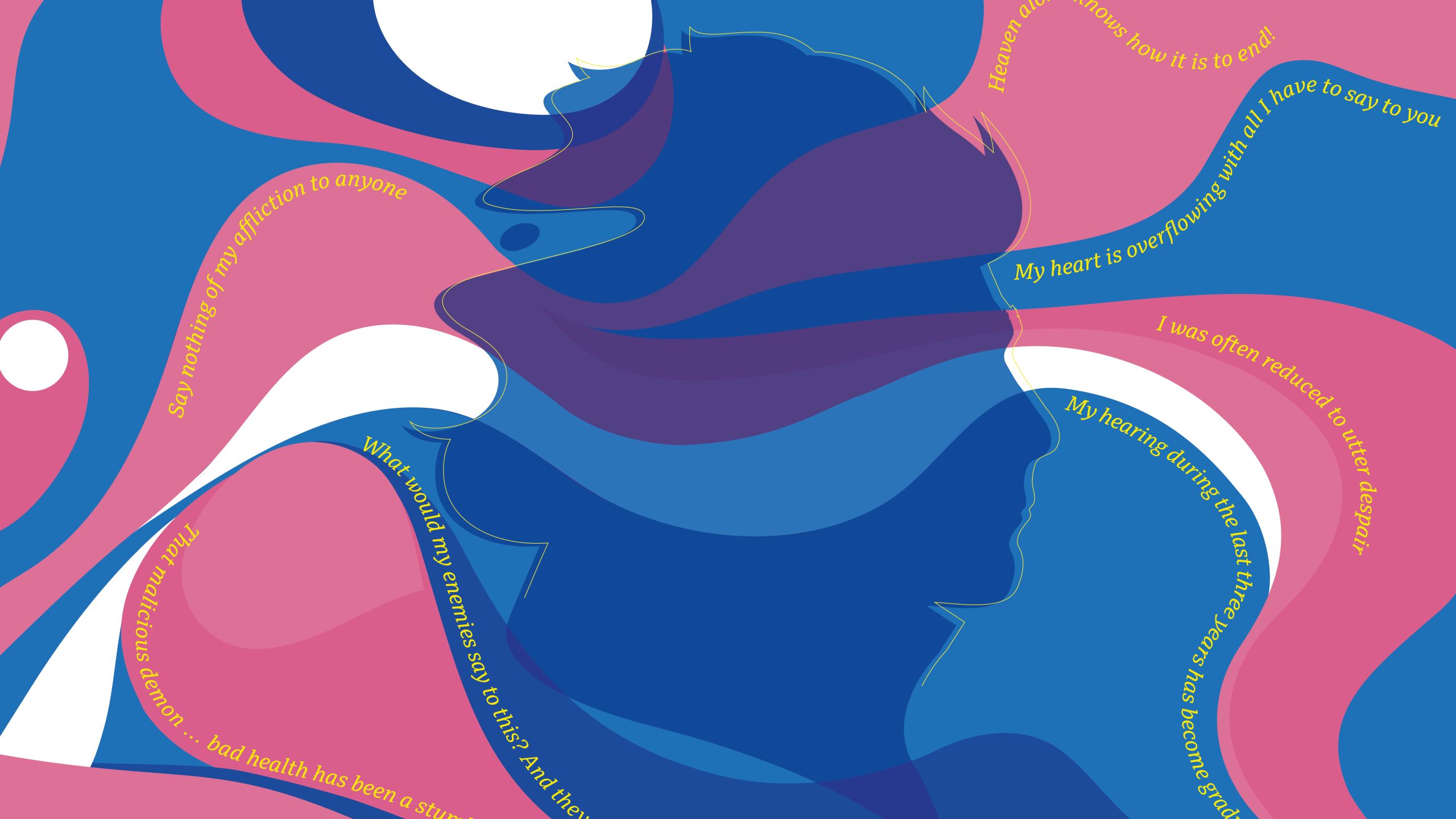

BBC Creative/Reenie Basova/BBC

BBC Creative/Reenie Basova/BBC

The ‘Fate’ against which Beethoven famously struggled only conspired to make things worse. Above all there was his deafness. Beethoven seems to have become aware of this as a growingly serious problem around his 30th year. We learn of this in his much argued-over ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’, penned in 1802 during one of his solitary summer holidays. This remarkable document – somewhere between a last will and testament, a private diary entry and a suicide note – has something of the quality of Shakespeare’s famous ‘To be, or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet. In this anguished outpouring, which the composer kept hidden for the rest of his life, Beethoven struggles to come to terms with encroaching deafness, and the frightening sense of isolation that came with it. He confesses that despair brought him close to ending his life, and yet something stayed his hand: ‘The only thing that held me back was my art. Oh, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had produced all the works that I felt the urge to compose.’

One of the enduringly astonishing things about Beethoven is the way he was able to turn even such terribly negative feelings to artistic advantage. Could anyone who had never experienced such profound inner darkness and loneliness have created the Dungeon Scene in his only opera, Fidelio? The agony of the political prisoner Florestan, starved and light-deprived, facing heaven knows what fate, is brought to life with a direct pathos and force rare in opera. But there’s something else too: hope, for Florestan, is symbolised by his wife Leonore, who appears to him in an almost frighteningly intense hallucinatory vision. It’s pretty clear that Beethoven created this vision out of his own desperate longing and need. The thought that he might find a ‘precious wife’, like the one hymned in the opera’s final chorus, was one he clung to for a long time – at least until the fierce, protracted and deeply damaging custody battle with his sister-in-law for his nephew Karl was instigated in 1816.

The house in the village of Heiligenstadt, then just outside Vienna, where in 1802 Beethoven wrote his ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’: the document in which he expressed the grief and torment he felt as a result of his increasing deafness, and revealed that he would have taken his own life were it not for his art (Lebrecht Music & Arts/Bridgeman Images)

The house in the village of Heiligenstadt, then just outside Vienna, where in 1802 Beethoven wrote his ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’: the document in which he expressed the grief and torment he felt as a result of his increasing deafness, and revealed that he would have taken his own life were it not for his art (Lebrecht Music & Arts/Bridgeman Images)

It isn’t hard to hear evidence of Beethoven’s struggles in his music, in Fidelio, the Third (‘Eroica’) and Fifth Symphonies or, more alarmingly, in the ‘Serioso’ String Quartet, Op. 95, whose violent emotional dislocations and seeming non sequiturs might well suggest a mind struggling to maintain its balance. And yet, through all this runs an echo of that thought expressed in the ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’: that the one thing that held Beethoven back from despair and self-destruction was ‘the urge to compose’. The act of creation, which Beethoven seems to have regarded as in some way God-given, gave him access to something in which he found strength and a sense of direction, even in the inkiest darkness. Who or what that ‘God’ might be isn’t always easy to tell. Beethoven was brought up a Roman Catholic, and his religious observation seems to have increased in his last years. Nevertheless he was also capable of invoking the philosopher Socrates as a model, giving him parity with Jesus, and, fascinatingly, it is quite possible that he read the ancient Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita; he certainly copied out parts of it in his notebooks.

Whatever the exterior stimulus, Beethoven’s music can appear not only to depict, but even to embody the process of finding inner strength. This is especially the case in the works of the ‘late’ period, after the final defeat of his former hero Napoleon and the obliteration of what remained of democratic revolutionary France – after which, finding an avowed democrat in neo-conservative continental Europe was about as easy as finding an unreconstructed Marxist in the years following the collapse of the Berlin Wall. The penultimate Piano Sonata, Op. 110, contains in its finale a kind of spiritual testimony in music. The movement begins in minor-key darkness, fragmentary ideas groping for some kind of clarity. Eventually this stabilises as a profoundly expressive aria for piano, marked Klagender Gesang: ‘Song of Lamentation’. From this a brighter, major-key fugue emerges, building towards the light; but at its height it falls apart, leading to a return of the Klagender Gesang, now in a remote key, its phrases broken like a voice breaking under severe emotional strain: the marking is ‘Ermattet, klagend’ – ‘Exhausted, weeping’. But then comes stillness, a single chord repeated – from which the major-key fugue emerges again, now marked ‘Nach und nach wieder auflebend’ – ‘Little by little returning to life’.

“Beethoven’s father, Johann, was an alcoholic bully, who beat little Ludwig savagely and thought nothing of dragging him out of bed in the middle of the night to play for his drunken cronies.”

Almost certainly unknowingly, Beethoven has charted here stage by stage (and, in places, word by word) the same process of falling apart, exhaustion and weeping, resignation and gradual return to life described in the classic account of the medieval Tibetan Buddhist visionary Milarepa. But he needn’t have looked so far for confirmation of his own voyage of discovery: the Spanish monk John of the Cross describes something very similar in his description of the ‘Dark Night of the Soul’. And the story of the humiliation, abandonment, death and resurrection of Christ is a powerful archetypal backdrop. Once this pattern has been identified, it can be made out in other works too: in the final Cello Sonata, Op. 102 No. 2, in the String Quartet, Op. 132, and in the huge ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, Op. 106, more a symphony for solo piano than a piano sonata. It is also possible to hear the variation movements in many of Beethoven’s greatest works as explorations of a meditative journey, where the circular form (each variation as a new perspective on the given theme) resembles T. S. Eliot’s wonderful observation in The Four Quartets (partly inspired by Beethoven): ‘We must be still and still moving into another intensity.’

If what we have here is, as I believe, a representation of how Beethoven found meaning, hope and direction in moments of spiritual crisis, perhaps it provides a pointer to how he overcame what most of us would think insuperable obstacles. In 1802, in the ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’, he tells us of the agony of being unable to hear a shepherd piping or singing in the distance, yet six years later he depicts both, exquisitely, in his ‘Pastoral’ Symphony. The finale of the last Piano Sonata, Op. 111, contains ethereal filigree textures unlike anything in piano music before, yet it dates from at least a decade since Beethoven had been able to hear a piano at all, and he had never heard the newer pianos, with increased sustaining power, capable of making these sounds. Darkness and pain without, calm strength and light within – perhaps the greatest miracle is that this intensely isolated man, tormented by tinnitus and all manner of bodily ills, found the means to express this in music, ‘from the heart … to the heart’ as he put it on the title-page of his Missa solemnis. There is a moving account of how Beethoven improvised for the pianist Dorothea von Ertmann, who was at the time paralysed by grief after the death of her infant son:

After the funeral of her only child she could not find tears … General Ertmann brought her to Beethoven. The Master spoke no words but played for her until she began to sob, so her sorrow found an outlet and comfort.

The miracle is that Beethoven’s music can still do that for us today, nearly two centuries after his death, and at the same time give us pointers as to how he found the means to do it. That, more than anything else, is why he still matters today.

Stephen Johnson is the author of books on Bruckner, Mahler, Shostakovich and Wagner, and a regular contributor to ‘BBC Music Magazine’. For 14 years he was a presenter of BBC Radio 3’s ‘Discovering Music’. He now works both as a freelance writer and as a composer.

This article was originally written for the BBC Proms 2020 Festival Guide, which was not published this year owing to the change of programme following the coronavirus epidemic.

Produced by BBC Proms Publications